Theory X and Y describe two contrasting models of workforce motivation and behavior. They were created by Douglas McGregor in the 1960s. According to these theories, there are two types of employee behaviors that can be encountered. Theory X behavior is driven by extrinsic motivation, while theory Y behavior is driven by intrinsic motivation.

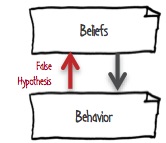

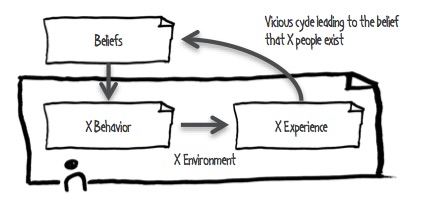

Many people believe that there are X or Y people, showing X or Y behavior because of an X or Y identity.

Based on this conclusion, people create environments that deal with X or Y people. For example organizations establish supervision, performance evaluations and bonuses to extrinsically motivate X people. Or they create self-organized teams for Y people.

Both organizations and people typically prefer Y behavior. So why do we have so many X behavior in companies, though no one really wants it?

The problem is that we derive the identity of people from our observation of their behavior. But the behavior is not just a result of what people believe in – it is also a result of the environment’s behavior. This leads to a vicious cycle: people show X behavior because of the environment. This leads to X experience, building the belief that there are X people, leading to more X behavior.

We question the assumption that there are any X people. We all show Y behavior in our areas of interest (e.g. soccer, dancing). Bluntly spoken: While no one really wants an X organization, we have them because we believe in the existence of X people. Which are not there. We have X organizations no one wants because of a phantom.

We question the assumption that there are any X people. We all show Y behavior in our areas of interest (e.g. soccer, dancing). Bluntly spoken: While no one really wants an X organization, we have them because we believe in the existence of X people. Which are not there. We have X organizations no one wants because of a phantom.

How do we get out of this dilemma?

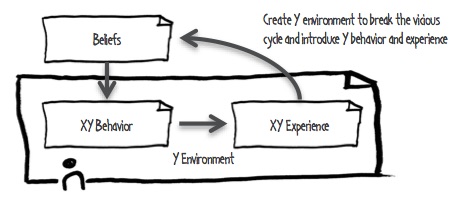

We cannot change the people’s beliefs nor their behavior. We can change the environment, though.

To go from an X organization to a Y organization, we create an environment with Y behavioral patterns. To bootstrap this, we need some innovators who are willing to establish a Y environment that supports making experiences.

Generally, agile patterns are one way to establish a Y environment. For example, an environment that establishes a pull planning technique and retrospectives fosters Y behavior and Y experiences.

To overcome the vicious cycle, the environment needs to embark on a journey that continuously introduces Y experiments and fosters experiences – until the Y behavior is dominant. At this stage people will start to believe in Y patterns. Then we will have turned the vicious X cycle into a positive Y cycle.

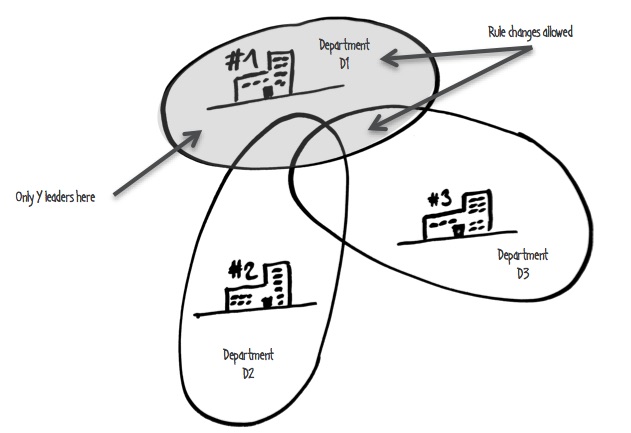

So far so good. How do we create the Y environment? This is where leadership comes into play. It starts with a leader who has the vision of a Y organization and the power to start the journey of Y experiments and experiences. His main responsibility is to initiate the journey, to support it and to guard it.

For example, a department leader starts with a team of people interested in Y patterns. The department leader supports this by showing and bootstrapping Y behavior. Frameworks like Scrum help to do so. Moreover, the department leader encourages the team to question existing rules and establish new ones. This leads to behavioral changes in the periphery of the team. Therefore the department leader supports the journey by communicating to others.

As the example shows, rules will be changed on the way from X to Y organization. All rules must be open to question them; there is no exception to this rule.

A Y environment does not mean that the whole organization works according to a Y behavior. It means that Y experiments are encouraged and supported, and that rule changes in the periphery are supported.

E.g. a team creating a new product using rapid prototyping currently must obey a purchasing process optimized for large batches. Leaders should support questioning this rule and establishing one that supports the team’s needs.

If we want Y behavior we need a Y environment. Y leaders sponsor this environment. If individual leaders stick to the X environment, we don’t get a Y organization. In these cases the organization needs to decide between the X leader or the Y organization.

The ideal case is that the environment is established for the whole organization. If that is not possible interim solutions can be chosen. One example is to create an independent business unit. Another is to explicitly manage the interdependencies on the periphery, e.g. translate Gantt Charts into Kanban and vice versa. Another example is a Y department manager who translates traditional bonuses this into profit sharing of the results of the whole department. However, the translation creates overhead and waste. It can also be a pitfall if the interim solution stabilizes.

The change from an X to a Y organization needs experiments to create Y behavior and experience. This needs bold leaders creating an environment in which Y experiments and rule changes are possible. If they don’t, change won’t happen. As an organization, it is up to you. Are you ready?