8 Perspective of a transformation

Chapter 2

Chapter 2: The realization

Put yourself in Manfred's shoes. He is the product owner of the teams, who is just moving into his new role as division manager. Experience the same events as in chapter 1, this time not from Katharina's point of view, but from Manfred's.

Scene 1: Thoughts and plans

Manfred stood at the window of his office and looked out at the open-plan office opposite. He could hear the quiet hum of the air conditioning and the clicking of keyboards. He noticed the subtle signs of unease among the team members. Some seemed anxious, others appeared to be engrossed in intense conversations.

While he was collecting his thoughts, he noticed Katharina walking through the rows of desks. She seemed calm, but he thought he detected a trace of concern in her eyes. He remembered the conversation they had had a few days ago and knew that they both shared some concerns and wanted to get down to business.

Manfred leaned back in his office chair and thought about his notes:

The leadership vacuum in the "MUH2000" team was palpable, the first questions were raised as to who would make decisions regarding the further development of the product, and he knew he had to act quickly. He thought of Julia, Magnus and Felix, three younger colleagues who had already worked hard in the past to keep a strategic eye on the development of the product. Could they take on the role of Product Owner and fill the leadership gap? Would they be up for the challenge? How should they work together? And what would there be conflicts about?

On the way to his next appointment, he thought about it for a while. The corridor he crossed stretched the entire length of the floor and provided an excellent view of the teams' work areas. Katharina was standing right next to a group of developers. Ah, that's just what I need, he thought to himself and walked straight towards her;

"Katharina," he greeted her and stopped next to her. "Can we talk for a minute? I've been thinking about the PO role. Instead of appointing a new Product Owner for all teams, why not have a separate PO for each team? Three people who can be closer to the action and understand the specific needs of each team." He was pleased to have Katharina on board. Some sparring and an independent opinion would certainly do him good. What's more, Katharina's support could keep his back free during implementation.

Katharina took the ideas well. "That could work," he heard her sympathetic reply. That made him feel better. He was less pleased when Katharina continued: "For this to work properly, we first need to better understand the product and the value stream."

She was certainly right to object. A closer look at the context would help to evaluate the idea he had in mind. But he also knew that he didn't want to wait long; the duties and day-to-day business of his new role as division manager would quickly catch up with him:

So he had to act quickly and send a signal for change if he wanted to give his idea a chance. And then there was the question of backlog maintenance. This was already working in a more distributed way. But he still had this hat on. How long would he be able to continue performing his old tasks as a product owner while he was still finding his feet in his new role? And to be honest, the other managers and division heads already saw him in his new role and demanded his attention. So time was of the essence.

"That sounds like it could take a while," he summarized his concerns to Katharina. "In the meantime, who will make the important decisions with the team and provide guidance?"

They discussed a few more details of the idea of having three POs. As he continued on his way down the corridor, Manfred was relieved. The future of the "material master" product looked promising overall. He was happy to play his part. However, the pragmatist in him also realized that there was still a lot to do and that he still had many questions to answer.

Katharina would still conduct interviews with individual team members to get an idea of the situation, the needs and the willingness of the people. Obtaining these perspectives is important in order to obtain a legitimized status quo on which a change like this can be based.

What have we experienced here?

Manfred feels the pressure to make decisions about the management structure of his team. He shares his thoughts with Katharina and they discuss the pros and cons of appointing multiple product owners. Katharina emphasizes the need to understand the product and the value stream in order to make the change sustainable and effective. Manfred recognizes that quick action is required, but also that many unknowns still need to be clarified. There remains a sense of urgency, but also uncertainty about the best way forward.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

Change is never linear and rarely simple. They are often associated with uncertainty, ambivalence and tension. Claes Janssen's model of the "Four Rooms of Change" illustrates this process impressively. In this scene, we observe Manfred as he navigates through the different "rooms".

Manfred's position at the window, from which he observes the open-plan office, can be seen as a metaphor for the room of "contentment". He reflects on the current situation and realizes that a change is necessary, but does not yet have a clear plan of action.

When he feels the pressure to make quick decisions and faces the challenge of appointing multiple product owners, he enters the room of "denial". He recognizes the need for change, but is unsure about the exact direction and impact of these decisions.

The conversation with Katharina can be interpreted as entering the room of "chaos". There are many unknowns, discussions about different approaches and the need to better understand the value stream and the product. It is a state of transition and uncertainty.

Manfred has not yet entered the room of "renewal", but the foundations are being laid. The discussions, the reflection and the gathering of perspectives are necessary steps on the way there.

Like Manfred, organizations also go through these phases when they are undergoing transformation processes. Leaders need to recognize which "room" they are currently in and what support they need to get to the next room. Understanding this process can help to make changes more effective and take those involved along for the ride. The four rooms model provides helpful guidance. It reminds us that change is a continuous process and that each step - whether uncertainty, reflection or action - makes an important contribution to the overall transformation.

Back to the top of the page

____

Scene 2: The experiment

After the weekly team meeting, Katharina stayed in the meeting room and asked Manfred for some time. "I've got half an hour left, then I'll be with the divisional managers in the budget meeting," Manfred offered her.

"I've conducted five interviews in the last few days and I'm slowly getting a picture together," Katharina opened. "I wanted to let you know briefly about this and also hear whether you share my impressions."

"I had prepared a summary beforehand, but it sounds like a general accusation, so I'll say this with all due caution and ask you to listen carefully. Don't take it as an accusation. The employees have the impression that there is a lack of direction and orientation. They also complain that the prioritization of features does not match the market demand from their point of view. And when they need decisions, they take a long time, which wastes valuable time, especially when it comes to architecture issues. Can you understand that?", she concluded her short report.

Manfred held back and tried not to let the anger he felt about the feedback show towards Katharina, whom he held in high esteem. He could guess who had complained to Katharina about which individual decisions and had used the opportunity to look for shortcomings in the leadership, even if they had made their own mistakes. "Well, not everyone likes every decision. Even technical decisions cause resentment among those who prefer the other technology. That's normal. Our products are coming too slowly, that's true, but I can't see that management decisions were the reason for this."

Katharina sensed Manfred's struggle for neutrality and composure, while inwardly he perhaps wanted to answer differently. "Let's think about whether this could work better with the idea of the three product owners. I don't want to revisit the past with you. It's over anyway. Your employees give me the impression that a different PO constellation could be helpful."

"I think so too," Manfred replied. "But the idea is also tempting because it's different and new. It's difficult to separate the two mentally, and we would have to find clues to tell us whether it would only be different or better if we implemented the idea."

Katharina went to the whiteboard in the meeting room and divided the area into six fields. "We're actually discussing an organizational development experiment or a change experiment. I have a visualization that helps you to sort your thoughts. It's called the Experiments Canvas, based on Lean Change Management."

"Please slow down. Experiment is a difficult word in connection with teams and people. We don't want to try things out here until we get it right," Manfred expressed his concerns;

"I can reassure you, Manfred. Experimenting here doesn't mean bumbling around; on the contrary, it refers to taking a more scientific approach. It means formulating a hypothesis about what is to be achieved and determining whether this assumption will be accepted or rejected after a predetermined period of time. It is therefore a definition of change with success and termination criteria. This is 'cleaner' than much of what we usually do in and with organizations."

"OK, let's get going then. I don't have much time before I have to go on."

"In the Status Quo field, I record what describes the current situation that needs to change. That's where the late product delivery, unclear direction, delayed decisions and so on end up." Katharina labeled the field at the bottom left of the canvas. "At the top left, we formulate the vision and record what the good world will look like once our project has been successfully implemented. I'll make a quick sketch with the three POs in it." Katharina drew

"What are the other fields called?" Manfred's impatience kicks in;

"From our conversation just now, I would particularly like to describe the 'Indicators' field at the top right. This is where the indicators you mentioned earlier belong, which we use to determine whether something has really improved with the new composition of the POs. It probably needs to include something like 'quick decisions', although this is still too vague for me. The fact that the POs coordinate their requirements is certainly also a criterion. And if the three of them start to act as a committee, then that's an indication that things are going wrong."

"That's true, if the decisions take longer than before," Manfred remembers. "I really have to go now. I don't want to be late for the budget meeting. We have to continue next week. Can you transfer this somewhere where we can continue working digitally? We can't just leave it on the wall here," he says goodbye;

What have we experienced here?

In an open dialog, Katharina shares her insights from feedback from team members with Manfred. She emphasizes the importance of clear guidelines and quick decision-making processes and introduces Manfred to the concept of the "experiment canvas", a tool for structuring change projects. Despite initial defensive reflexes, Manfred recognizes the need for a structured approach to change using a verifiable approach and embraces the format.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

Transformation is a process that is often guided by the idea that with the right approach, everything will be seamless and without setbacks. But in reality, any change, especially in complex systems such as companies, is a challenge that is not linear. This is where the J-Curve comes in.

The J-curve shows impressively that when a change begins, before the hoped-for improvements occur, a decline in performance can often be observed. In scene 2, we see exactly this point: Manfred and Katharina are aware of the need to change their management approach, but are also faced with the uncertainty and potential setbacks that this could entail. Creating an experiment, as Katharina suggests, is one approach to anticipating and managing this temporary setback. It ensures that the change is systematic and verifiable. This also reduces the risk of the change running out of patience and being abandoned, for example;

The idea of "micro J-curves" is also special here. Instead of going through a large, monolithic transformation process where the low point is difficult to predict and control, experimentation allows for the division into many smaller steps of change. Each of these steps has its own small J-curve, starting with a hypothesis, followed by a short decline and finally an improvement. This approach not only increases control and predictability, but also allows for faster adjustment and correction if a step does not go as expected.

If we use the J-curve as a metaphor: Manfred and Katharina are just at the beginning of one of these micro J-curves. They recognize the initial challenges and are aware of the potential "downhill slide" that lies ahead before the hoped-for improvements occur. Experimenting and establishing clear criteria for success - such as faster decision making or better coordination between POs - serve to minimize the depth and duration of this trough. The goal is to accelerate the "recovery" and subsequent climb to a better state.

By breaking it down into smaller experiments and steps, the team can continuously learn and adapt instead of being trapped in a long, unpredictable change process. This approach emphasizes the importance of responsiveness and adaptability in transformation processes.

Overall, this scene shows that change is not easy and does not always lead directly to the desired result. But with the right approach, awareness of the challenges and the right tools, it can be managed and led to success. Understanding the J-curve and systematic experimentation, particularly in the form of micro J-curves, are crucial building blocks in this process.

_____

Scene 3: Let's try this

Manfred and Katharina had already been working on the design and detailing of the experiment canvas for two hours. The insights from Katharina's interviews had made it clear to Manfred where the journey needed to go. He was pleased with the measures and hypotheses that had already emerged on the board. From his perspective, the decision to appoint a product owner for each team had already been made and he was fully aware of the challenges and opportunities this decision would bring.

After a much-needed coffee break, Katharina spoke up again. "Manfred, I've been thinking about the Product Owner Team Experiment again," she began.

Manfred nodded. During the break, he had withdrawn a little, but couldn't really switch off. He was thinking about his duties as division manager. After all, he was responsible for ensuring that his division continued to develop in the interests of the organization. "Me too, Katharina. It's an experiment, but it's also a big step, and I'm wondering how we can get some traceability and clarity into it. After all, we are not the only department in the company and we have to communicate with our stakeholders."

Katharina leaned forward. "I understand the idea and see this as a great opportunity. Self-organization and the close integration of product owners will be crucial. I already have ideas and approaches for this." Katharina wrote a short note on a Post-It and attached it to the topic backlog.

She then continued: "But let's first define the indicators for the success and failure of the experiment together and derive the vision. Then we can communicate here in the department and in the company why we are making the change and also conduct a fair experiment with clear guard rails and termination criteria as well as orientation points for possible adjustments."

Together, they filled in the last few points in the experiment canvas. The last 90 minutes had flown by. Manfred was glad that the basis for communication was now in place. They had deliberately changed perspectives several times and incorporated various questions and concerns from different stakeholders - both from the department and the company - into the experiment. That gave him a good feeling.

His eyes now fell on Katharina's post-it and he frowned. "But how do we make sure that the product owners work together effectively and don't just think about their respective teams and pull in different directions?"

Katharina smiled. "By setting clear expectations and guidelines. And by organizing regular meetings where they can share their experiences and learn from each other. We have to manage all of this in such a way that we set a framework and provide guidance without taking responsibility away from them. Our approach to this could be a Kanban system, for example, so that our product owners focus on the stakeholders of our product and think more about the market and not so much about internal departmental concerns. This also includes mechanisms for making difficult decisions in the event of disagreement."

The discussion went on for some time until it felt like a plan to both of them. In the end, they were in agreement. Manfred's final "That sounds sensible. Let's try it!" sounded a bit Hollywood, so Katharina giggled quietly.

What have we experienced here?

Manfred and Katharina deepen their thoughts on the introduction of multiple product owners. Manfred's concern for clear structures and orientation in the change process becomes clear. Manfred and Katharina work together on clear guidelines and goals for the process. In the end, they feel well prepared to try out the new approach.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

Change is often a process characterized by ups and downs. The J-curve model visualizes that changes often initially lead to a decline in skills or productivity, for example, before the hoped-for improvements occur. It is a reflection of how change happens in reality and not how it should ideally happen. Experimenting with a structured and verifiable method provides an opportunity to approach change in a methodical and controlled way. It shows that you need to be aware that there may be setbacks before the desired improvements are achieved.

The detailed elaboration and communication of change projects are crucial for their acceptance and success. It is essential to define clear indicators, guard rails and goals. The J-curve (see above) reminds us how important it is to recognize and accept the "patience phase".

Managers and other stakeholders must be prepared to navigate through this phase without prematurely abandoning the change initiative. It is about building trust in the change process, communicating changes transparently and providing those involved with the tools they need to successfully shape the transformation.

...

______

Scene 4: Maybe it actually works

"The three of them are at very different points in their development," Manfred said to Katharina. The question of the probable dynamics in the Product Owner team had been on his mind since their exchange about the Experiments Canvas yesterday. "Our 'framework', as you say, has to be very individual because the three of them each need different support."

"Absolutely, that's how I see it too. Our challenge is to support the POs individually and at the same time form a team that sees itself as the overarching driver of our portfolio," concluded Katharina.

Katharina suggested the potential Product Owner candidates, Julia, Magnus and Felix, to call to you brieflyto get their opinion. That's what Manfred really appreciates about Katharina's approach: pragmatically examining theses with others, identifying and integrating the need for change and then, if necessary, discarding approaches completely.

A short time later, everyone was sitting in the conference room. Julia, Magnus and Felix seemed excited, but also a little unsure. Katharina opened the meeting. After the initial idea had been shared, she asked how the three of them would see and feel in their new role as product owners.

Julia, always direct and honest, spoke up: "I think we should define clear roles and responsibilities. Each of us has different strengths and we should use them."

"Yes, we see it that way too. Those are two very important points: The responsibilities, which should be the same for all three of you, and then the way in which they are carried out. They can and must be different because you three are different people and your experiences are also very different," Katharina replied, glancing sideways at Manfred.

Magnus nodded in agreement. "Yes, and we should also have regular check-ins to make sure we're on the right track."

"What do you mean by check-in? I always use the term for the first few minutes of a workshop or meeting." Manfred didn't want to leave any ambiguity in this meeting. He had also seen Felix and Katharina frown briefly.

"Well, we often - probably every morning - have to have a quick chat about what's on, what's burning and where we can help each other," explained Magnus.

Felix pointed out that training for POs could be useful.

The ideas went back and forth. Katharina took notes and couldn't keep track of everything that was said and what was going through her mind. Very good, all the things that came up, she thought.

Manfred observed the conversation with the pride that his people were having the right discussions here. It wasn't just about their own concerns in the field, but above all about the portfolio and the contribution to customers and the company. Maybe it really does work, he thought.

Katharina suggested concluding the meeting with a session on future working methods and the biggest challenges. In this way, everyone would be involved in writing and there would be a stand afterwards that could be photographed. Manfred took an active part in the discussion and felt encouraged by the team's energy and commitment.

As the meeting drew to a close, Manfred left the room feeling confident. He was ready to tackle the next phase with full confidence in his PO team. Now it was time to get the "official go".

What have we experienced here?

Manfred and Katharina discuss the individual challenges and opportunities of potential product owners. By meeting Julia, Magnus and Felix, they gain valuable insights into their perspectives and expectations. Manfred feels encouraged by the exchange and confident about taking the next step. Manfred appreciates the proactive and solution-oriented approach of all those involved and is therefore confident about the upcoming change.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

In this scene, we encounter one of the central elements of every successful transformation: involving people and shaping things together. The employees - in this case Julia, Magnus and Felix - are at the heart of every change. By actively involving them in shaping the future path, Manfred not only creates a basis for acceptance, but also enables the transformation to be based on genuine understanding and commitment.

Another critical element that is emphasized here is the clarity of responsibilities. In any change process, especially in complex organizations, lack of clarity can lead to confusion, overlap and ultimately inefficiency. By ensuring that everyone knows (as well as possible) what is expected of them and how they contribute to the overall vision, the transformation is strengthened and facilitated.

The importance of regular communication cannot be overemphasized. As Magnus rightly pointed out, daily check-ins not only enable the exchange of information, but also provide opportunities to offer support, discuss challenges and find solutions together.

Finally, Manfred's role as a leader shows that true leadership is not about giving orders from above, but about encouraging, supporting and giving his team the tools and space they need to succeed. His trust in the team and his openness to their ideas are key to their shared vision for the future. Manfred demonstrates important leadership principles through the way he leads.

At wibas, we believe that it takes many "ingredients" to make a change successful. We use this visualization to think about the "success factors of change" in everyday life:

The scene shows the importance of a collaborative and inclusive approach to transformation, based on clear expectations, regular communication and supportive leadership. This also creates the basis and psychological security to talk about and address strengths and weaknesses. In the spirit of "strengthening strengths" and "weakening weaknesses".

-------

Scene 5: The management circle and the experiment

Manfred entered the conference room where the division heads were already gathered. According to the agenda, they wanted to discuss budget issues and strategic projects. The experiment was so important to Manfred that he used the welcome session to add his topic to the agenda. Some of his colleagues were concerned about the timetable, as the divisional manager meeting was often overrun.

Manfred was not dissuaded, however. His standing in the company had to be good for something, he thought, before he began: "I'm starting an experiment in my department, initially for three months. I want the teams that I've had as PO so far to each have a dedicated PO."

"Barely a division manager and already increasing the number of people," he heard a comment in a joking tone from the other side of the table. Or was it biting? Manfred didn't give himself time to think about it.

He briefly checked that the experiment canvas he was projecting onto the screen was clearly legible.

"Experiment means that we look at the effect every month. If the effect is negative, we end the experiment after three months. If the indicators look good or ambiguous, we extend it once for another three months. After that, it's either hop or topp. Hopp means we go back to one PO; topp means we stay with three POs."

The facial expressions reflected the expectedly different levels of approval for his presentation. Manfred interpreted "Hear, hear!", "That's not going to work!" to "Brave, Mr. Colleague." into the faces of the audience. Questions were raised about the effect on the staffing plan, on the budget, on the pay scales of the people employed, on the ability to deliver. And also: who the three POs should be.

Manfred was able to answer these questions well. The preparation had paid off. And the canvas condensed the key facts into an overview that was also suitable for the management meeting. Manfred was in the flow.

After a few minutes, the controller put it in a nutshell: "First of all, these are not additional jobs and no additional costs. It's actually all your decision, Manfred. So we'll hear from you in three months about the outcome, won't we? Unless, of course, we notice the improved performance in your area, which will certainly get around quickly. So, I have nothing against it."

Even if it wasn't the controller's decision to accept Manfred's plan, his comment seemed like a decision made by the group. They were happy to have dealt with the topic quickly without it turning into a fundamental discussion.

Manfred paused briefly, but skillfully used the resulting pause to make a point with: "Thanks for the OK, I'll present the PO topic again next quarter" and clear the stage for the next topic. It went through his head.

Manfred participated enthusiastically in the following agenda items. The meeting only lasted a little longer than planned and so there was time to inform the new POs immediately afterwards.

Manfred called Julia, Magnus and Felix into his office. "Well, sometimes things happen very quickly," Manfred began, "We can start our experiment and I want to do it as quickly as possible. I've informed the department heads. There were questions, but no resistance. It's our thing - er, your thing now. With the support of Katharina and me, of course."

What have we experienced here?

Manfred informs the department heads about the PO experiment. After some rather factual questions, it is clear that the experiment can officially continue. He informs the future POs about the upcoming change and the role they will play.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

In this scene, we observe Manfred presenting and defending his transformative idea in a traditional leadership context. This brings to light some important aspects of transformation:

Communication is key: an idea or concept, no matter how brilliant, will only fall on fertile ground if it is communicated effectively. Manfred has focused on clearly presenting both the status quo and the target picture. He also emphasized alignment and an iterative approach to bring the other leaders along on the journey of change. It shows how important it is to communicate consistently and transparently during a transformation. At wibas, we remember this based on the success factors for change:

Leadership cannot be delegated: Transformations are often associated with uncertainty and resistance. We already discussed this in the last scenes using the J-curve. In times like these, managers cannot remain in the background and hope that everything goes well. Manfred's active role in defending the experiment shows how important it is to take the lead, face the questions and concerns and ensure that the team and the organization are going in the right direction. In doing so, he avoids falling into the change trap (i.e. delegating leadership tasks to others) described below:

Legitimization through review: Obtaining feedback and having other leaders review the change effort is not only a means of validation, but also a way to refine the approach and ensure that it is supported by the entire organization. It also shows how important it is to have a continuous review process during a transformation to ensure that the change is both relevant and effective. In this respect, we are continuously working on legitimization to avoid unnecessary resistance:

Legitimization through review: Obtaining feedback and having other leaders review the change effort is not only a means of validation, but also a way to refine the approach and ensure that it is supported by the entire organization. It also shows how important it is to have a continuous review process during a transformation to ensure that the change is both relevant and effective. In this respect, we are continuously working on legitimization to avoid unnecessary resistance:

Overall, this scene shows that transformation is not just about implementing new ideas or processes, but also about how these ideas are communicated, managed and reviewed within an organization. It is a constant balancing act between the new and the old, between progress and preserving what already exists. It requires both courage and diplomacy, and above all a clear vision and determination.

-------

Scene 6: A committee that must not be one

The decision had been made. The experiment with the PO team was to continue for at least three months. Manfred hoped that it would run for much longer and wanted to make it a self-runner. He believed in this form of distributed leadership as he had already practiced it himself as the product owner of several teams in the division.

However, the times since he became divisional manager had not been easy either. He always felt compelled to "step into the breach as PO", whereas he actually had much more to do in his new management role as divisional manager.

At the same time, there had also been an impact on the teams. The perceived lack of direction was a reproach that still stuck in his craw. After a few conversations with Katharina, he was able to give it a positive meaning: he had experienced first-hand what it was like to do too many jobs at the same time. This was another reason why he wanted to give the "Product Owner Team" experiment the best possible start. However, this also meant setting up a few things that might not be there at the moment.

He had shared his concerns with Katharina. She had listened to him and asked him to wait for the POs to ask for clarification. That had probably been the case quite quickly. That same week, he found himself in a workshop room with the POs with the aim of "establishing the starting point for the experiment". It had a reassuring effect on him that, as a divisional manager, he didn't have a prominent role at first. At the same time, his experience as PO seemed to be in great demand. He was looking forward to the working meeting and was excited about what the agenda promised:

The start of the workshop was as expected. The recap of the experiment and the exchange on strengths and pitfalls were constructive. And even more importantly, everyone was able to develop a similar picture of the experiment.

The section on the methodological starting point was exciting. Katharina had the group contribute their own experiences and discuss possible approaches. Manfred, for example, was able to contribute his Scrum knowledge and emphasize that there always needs to be a decision-maker and that the PO should never be a committee. This was also the point when they suddenly started talking about Kanban approaches to reduce delays in decision-making. It dawned on him that there was a trap in the Product Owner team. Katharina brought in various approaches, which they explored in small examples: e.g. viewing the product backlog as an upstream Kanban and thus discussing a process for competing ideas in the department's portfolio in order to then explore the right things in the spirit of the product ownership cited in Scrum. Over time, an overall picture of the collaboration emerged:

The step of creating a team canvas then suddenly came quite naturally. This not only clarified the objectives and necessary framework conditions, but also established a number of rules. For example, joint strategic and coordinative meetings of the POs (and other stakeholders) were regulated. However, emphasis was placed on ensuring that operational collaboration with the teams also took place in the foreground. In the end, it was about results and not about meetings. The fact that Manfred was more of a silent observer during this section, but was nevertheless asked for his opinion at essential points, made him happy and strengthened his confidence.

The section on sharing experiences was also nice. Manfred remarked that there had never been a real handover and that this had left a stale feeling. That was different now. After just under an hour, the feeling was gone and Manfred's experiences were incorporated into the new way of working. This was probably not only good for him as the former PO in terms of a handover, but also helped the new PO team. He had the impression that they knew they could approach him at any time and still "drive the bus themselves and no longer just for him".

What he hadn't counted on were the good comments from the team representatives when "challenging the approach". There were so many little things to consider. And at least he would never have thought of them himself.

He had already been a little worried during the preparations for the meeting when Katharina suggested that he invite other division head colleagues. After all, he had only recently pushed the experiment through in the divisional managers' meeting. And now he was supposed to defend it again - in front of the critics. Surprisingly, the group had been able to integrate the concerns well and he had been surprised by the feedback from his BL colleagues: "they had a good feeling that nothing would fall down" and even offered help "if there was a need for regulation at the interfaces". "Well," he thought to himself, "participation creates participation."

In the end, everything seemed to be coherent and well prepared - at least as far as possible. He felt a sense of relief. He knew what to look out for and felt that they were on the right track. He thought about working with Julia, Magnus and Felix and was convinced that they were the right people for the job - even if they would make some decisions differently to him.

After the meeting, Manfred remained seated for a moment. He looked out of the window and let his mind wander. This approach is new and untested, he thought, but it has the potential to revolutionize the way we work and bring us closer to our goals.

What have we experienced here?

Manfred and the future POs work out the basics and the methodical approach to collaboration in a workshop. They define clear roles, responsibilities and working methods, drawing on Manfred's experience as a former PO. Feedback from team members and other division heads is taken on board and integrated into the approach, which strengthens everyone's confidence in the experiment. Despite initial concerns, particularly regarding the involvement of external stakeholders, Manfred is ultimately convinced of the path taken.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

This scene highlights the fine art of navigating the complicated waters of a transformation. Particularly noteworthy are:

- Adaptability: The discussions about different methodological approaches, from Scrum to Kanban, show the need for a flexible approach to transformations. In a constantly changing environment, sticking to a single approach can be a hindrance. It is important to be open to different approaches in order to find the best way for the specific context and challenges of the organization.

- Recognizing challenges: Manfred's awareness of potential pitfalls and difficulties is crucial. Too often, such challenges are either overlooked or ignored, which can lead to unexpected obstacles. Recognizing and acknowledging these challenges from the outset allows you to be proactive and provide the right support.

- Avoiding diffusion of responsibility: While collective decision-making is valuable, Manfred emphasizes that it is crucial to define clear responsibilities. In collaborative decision-making situations, it must be clear who is responsible in order to avoid the risk of diffusion of responsibility.

- The balance between leadership and empowerment: While Manfred has a clear vision, he also recognizes the importance of empowering his teams. His trust in the PO team, coupled with his willingness to share his own experiences, shows how important it is to balance leadership with team autonomy.

- The value of collective knowledge: Involving team members and other area leaders emphasizes the importance of collective knowledge. An individual cannot see all facets of a transformation, but a group can provide a much more complete view of the challenges and opportunities.

- The subtle role of the leader: Manfred shows that true leadership does not always mean being in the spotlight. Sometimes it means staying in the background, listening and letting others contribute their expertise.

Successful transformation is therefore not achieved by having clear guidelines and instructions. It requires a combination of flexibility, recognition of challenges, clear responsibilities, collective knowledge and balanced leadership.

---------

Scene 7: Done! Really?

Manfred sat in his office and stared thoughtfully out of the window. The conversations outside filtered through to him, but he barely noticed despite the open door. His thoughts revolved around the last few weeks, during which the experiment with the Product Owners Julia, Magnus and Felix was running at full speed. All in all, things were looking good: The teams were working together more effectively and the POs were fulfilling their roles exceptionally well.

But today a customer had come to visit and, while praising the result, he had also noted that the delivery time had not been reduced despite the internal optimizations. That was a wake-up call for Manfred.

When Katharina entered his office, she immediately realized that something was weighing on his mind. "Manfred, you look thoughtful. What's on your mind?" she asked cautiously.

He took a deep breath and began: "It's the feedback from our customer today. Our internal changes are good, the team is working, but the end product we deliver is not improving in speed. And that's in line with some of the issues that other division heads raised at the strategy day."

Katharina sat down opposite him. "I've heard similar things from the teams. The internal processes are better, but we need to focus on the entire supply chain."

Manfred nodded. "Exactly. It's as if we've only tackled part of the problem. Maybe we need to think bigger." He remembered a statement from Katharina: "For that to work, we first need to better understand the product and the value stream." He paused for a moment, then continued: "Maybe we really need to think about the whole logistics value stream and how leadership and structure can work in such an extended environment."

The two of them engaged in an in-depth discussion about the logistics value stream and what management and structure would have to look like to meet these requirements.

The next day, Manfred gathered Julia, Magnus and Felix in a meeting room. "Our original experiment is working well," he began, "but we've identified a new challenge. What we have improved internally is not enough. We need to think about the entire logistics value stream and how we can adapt our leadership and structure."

The discussion that followed was lively and productive. Everyone had formulated the thesis that a major change was needed to meet the demands of the market and customers. And that meant involving others and "leaving your own backyard".

It finally dawned on Manfred that the previous management topic of "a PO becomes division manager and needs a successor" had been tackled in a promising way. But this had not yet been a transformation. A solution had been created for his leadership issue. He slowly realized the extent of this seemingly simple term from the change manager training: "Transformation: you have to experience it yourself to understand it," he grinned. Then the pragmatist in him came through: "Then I'll probably need the support of my management colleagues now. I can't go it alone for now."

What have we experienced here?

Katharina and Manfred realize that the real transformation is yet to come. They realize that the entire value stream must be considered in order to create impact for the customer. Other areas and overarching structures are also affected by the resulting journey.

And what does that have to do with transformation?

It often happens that further topics develop from an initial topic. In many organizations, we notice that added value is created across departments and divisions. And that's exactly when the exciting topics start.

This story so far has been about exactly that: an exciting first topic. And this is now getting bigger if we want to achieve more than just a reorganization of existing work. Then we are talking about a transformation that also affects the organization with all its individual parts. This is where the bigger journey can begin!

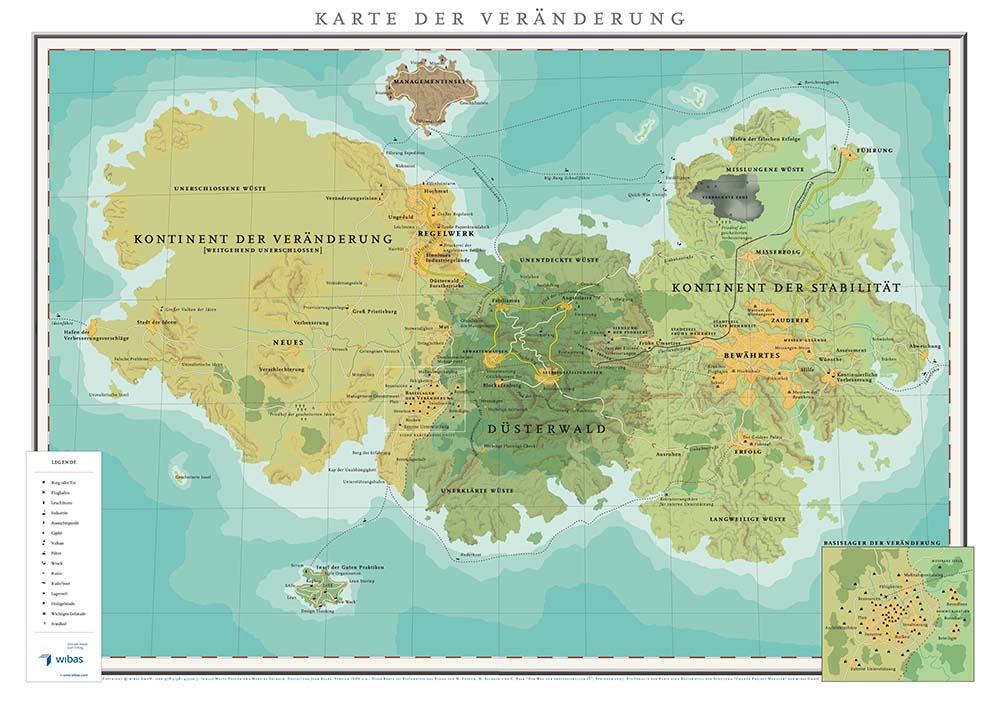

And this is more than a purely rational journey - as our "Map of Change shows":

Immerse yourself in history

Transformations are complex undertakings. Organizations that want to change sustainably and effectively in line with a target vision need to make more than just one isolated adjustment.

Chapter 1

Put yourself in the shoes of Katharina, an experienced change facilitator and systemic organizational developer. Katharina is also a trainer for change management trainings and she is led into her latest challenge by a former training participant.

Manfred: The determined division manager

Manfred is the division manager and former product owner of the company and leads it through a restructuring with his dry sense of humor. You will initially get to know his view of the events in chapter 1.

Katharina: The agile coach on site

Katharina is an agile coach and external consultant for the company. You will get to know her perspective on agile transformation in chapter 1.